In One Battle After Another, a character parrots one of the most recognizable phrases of the last half-century: “the revolution will not be televised,” from Gil Scott-Heron’s song of the same name.

One Battle After Another Story

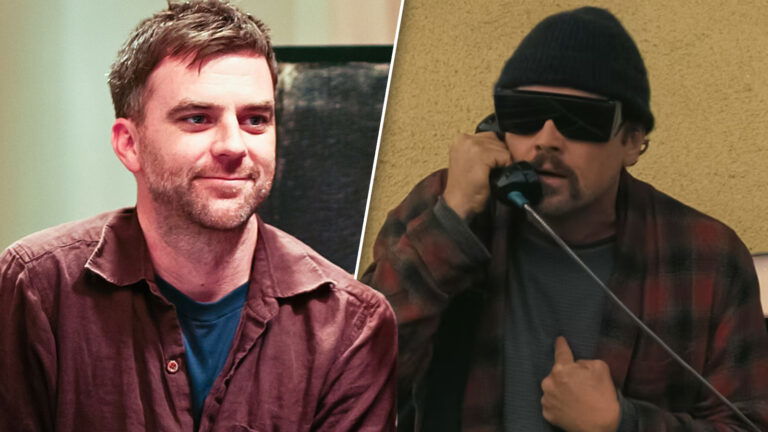

The phrase carries a campy air within the film, where it sounds like an empty platitude to us, while the person says it with their entire chest. It’s by design, as part of filmmaker Paul Thomas Anderson’s dissection of the messy contradictions and inherent weaknesses of America’s dodgy political ideologies.

On one side of the divide is French 75, a revolutionary group dedicated to the free movement of people, regardless of borders. Part of that group is Pat (Leonardo DiCaprio), a modest bomb-making specialist, and his fiery, reckless lover Perfidia (Teyana Taylor). Their explosive acts put them at odds with Colonel Steven Lockjaw (Sean Penn), a racist officer who fixates on Perfidia.

Sixteen years pass, and the cat-and-mouse game hits a fever pitch when Pat, now under the assumed name Bob, discovers that his daughter with Perfidia, Willa (Chase Infiniti), has gone missing. Although he had exited revolutionary activities long ago, he dives back into the underground network, only to discover a bevy of changes that seem determined to impede his search for and rescue of Willa.

One Battle After Another Review

It takes some time for One Battle After Another’s intentions to become clear. While Anderson’s world and characters are engaging, he initially obscures his cards behind a tense blend of chaotic action and dry humor. It can be confounding, but also transfixing. As we get to Willa’s disappearance, Anderson’s examination of sociopolitical fiction, reality, and the hypocritical and nonsensical gaps between them crystallizes.

The nonsense appears to start with Bob’s re-entry into the world of French 75 after nearly two decades. He’s long been disconnected from that world because of his need to go underground to escape Lockjaw and the ensuing self-medication and alcoholism to cope with the loss. Willa’s disappearance snaps Bob’s revolutionary instincts into place, but he doesn’t speak the language anymore, nor does he understand the systems installed in his absence.

Anderson gets a lot of comedic mileage out of the disconnect. One particularly funny sequence has Bob get increasingly frustrated at a contact who requires a password related to time. Bob tries to explain who he is and his circumstances, but the contact refuses to help without the password. “You’re violating my space right now,” the contact complains when Bob shouts at him.

A former comrade does help Bob, and when Bob asks about the password, the unhelpful contact returns with a silly platitude about time that reads like a self-help book passage. At the core of that ridiculously absurd exchange is a kernel of truth about the performative nature of modern revolutionary politics. Empty virtue-signalling platitudes overwhelm the end goal of genuine, transformative action.

Steven Spielberg Just Compared One Battle After Another With Stanley Kubrick’s Highest Rated Movie

While it seems like Bob is critiquing the younger generation of revolutionaries for their fecklessness, Anderson shows us that it came from somewhere. The film opens with French 75 commandeering an immigration detention center, and Perfidia holding Lockjaw at gunpoint, repeating phrases that wouldn’t sound out-of-place coming from Bob’s contact. While Bob and Perfidia were effective in their past, there were shades of posturing that may have dampened the seriousness of their work, which the subsequent generation would only expand upon. Anderson taps into that propulsive narrative force, the comic tension between intent and results moving the film at a remarkably speedy pace.

Leonardo DiCaprio is also an excellent conductor of Anderson’s exuberant direction. He looks, moves, and speaks like a disconnected, weathered man of his age, someone who would absolutely embarrass his teenage daughter just by existing. It’s a significant shift for an actor who’s been primarily suspended (some might say trapped) in youth. When Willa is in danger, DiCaprio snaps into action with a sharp, captivating focus in his eyes that levels off his comic beats. It helps to have Chase Infiniti playing his daughter, who infuses Willa with a steely, wise-beyond-her-years intelligence that DiCaprio plays very well off of.

Then, there is One Battle After Another’s take on political hypocrisy, focused on Lockjaw’s rampant pathologies. Lockjaw is an unrepentant racist who flaunts his perceived dominance as a white man over systemically oppressed people of color, specifically immigrants. His racism leads to his invitation to the Christmas Adventurers Club, a Freemasons-esque club “dedicated to making the world safe and pure.” (In other words, white.)

While he is elated by the invitation, Lockjaw has a problem: his obsessive attraction to Perfidia, which played a direct role in her separation from Bob and Willa. Lockjaw’s pursuit of them is more about reconciling what he would consider an affliction than justice. Sean Penn fully embodies that twisted framework, conveying confused toxicity and destructive menace through his ungainly movements and deliberately unconvincing strongman tone.

What Lockjaw fails to realize about his foolish ideology is that it ultimately spares no one. Yes, Lockjaw can weaponize the Army against Bob, the man who loved the woman that Lockjaw either loved or fixated on (and ultimately resented). White supremacy, however, takes no prisoners. It will defy decency, humanity, and plain old common sense to achieve its flawed objective.

One Battle After Another First Reactions: Will Leonardo DiCaprio Break Paul Thomas Anderson’s Oscar Curse?

It’s a very tricky dynamic to satirize, but Anderson succeeds in subtle and glaringly obvious ways. Ella Fitzgerald singing a Christmas hymn while a Christmas Adventurers Club member moves through a, well, underground railroad, is a subtle but deeply effective gag. Even better, and crueler, is how the club dispassionately, covertly dispatches its members who they deem insufficiently racist. Even with such a rotten core, Anderson frames white supremacy as another contradictory form of political performance, except that its unseriousness allows it to mask its darkest intent. It’s the horrifying inverse of revolutionary performative activism.

Is One Battle After Another Worth Watching?

While the contexts are different, Scott-Heron’s protest anthem and One Battle After Another both speak to a truth about contemporary revolutionary politics: it’s hard work that isn’t suited to passive participation or performative posturing. In fact, revolution, or even basic meaningful change, will likely collapse under the weight of either, or definitely collapse under both.

We’re living in a time where bad actors are exploiting our collective inability to discern the truth. Frankly, we can’t afford messy contradictions when it seems like the social fabric is a tug away from dissolving into strands. Speeding alongside Anderson’s black comedy is an urgency to clear out the noise and malaise and embrace decisive action. If not, we will be stuck in a never-ending stream of battles until there’s nothing and no one left.

One Battle After Another opens in theaters on September 26.